There is no doubt that the interactive media industry (primarily gaming) is a massive force in today’s world. It’s estimated that last in 2016 the money spent on games reached $92b, which is more than consumers spend on movies ($62b) and recorded music ($18b) combined. This means that the games industry is now five times larger than the music industry, and 1.5 times larger than the film industry. Last year the gaming industry directly and indirectly employed nearly 200,000 people with employees earning an average of $100,000 in comparison to the average US household income of $67,000. Surprising? Maybe not. There are many ways to game now, with the widespread use of mobile devices, on top of desktop gaming and dedicated consoles. So obviously we can’t ignore it – we must celebrate it, and be more in tune with how it works, where it’s going and how to get involved.

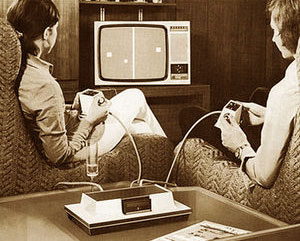

Computerized gaming saw its first light in the 1940’s alongside other developments in the world of electronics and computer processing. Slowly, the interest in how far games could be taken led to public access to playing at home.  The first console game available to consumers was the Magnavox Odyssey in 1972. It was very basic and involved square dots that could move around depending on the chosen game. The screen was monochromatic (black and white) but the package included different plastic sheets that would be placed over the TV screen to give the gamer special visual displays that the dots would then “interact” with. This era is considered the first generation of games.

The first console game available to consumers was the Magnavox Odyssey in 1972. It was very basic and involved square dots that could move around depending on the chosen game. The screen was monochromatic (black and white) but the package included different plastic sheets that would be placed over the TV screen to give the gamer special visual displays that the dots would then “interact” with. This era is considered the first generation of games.

Soon after, the fresh gaming world was introduced to classics such as Pong, Pacman, Asteroids and Space Invaders in the late 70’s and into the early 80’s thanks primarily to the company ATARI. Graphics and gameplay were still very basic with static screens and crude characters. Players would interface with the units via a joystick or paddle, and often the keyboard was a main factor. This is known as the second generation.

Interestingly though, the US game industry suffered from the game crash in 1983, and many of the studios dried up and vanished. A key example of a major failure at this time was Atari’s E.T., based on the blockbuster movie. This game was a complete disappointment and couldn’t sell – thousands and thousands of units ended up in the landfill. It’s a fairly iconic piece of gaming history as it is often labeled the worst game ever made. Production and development in Japan, however, was just taking off and created a pretty healthy import market. This helped keep the arcade scene alive and well for several more years, and absolutely raised the consumption of console gaming at home. Nintendo was created during this time, and released its first home console, the Family Computer (Famicon). This device was a hit overseas, and when when distributed to the U.S., it was re-branded as the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES), and instead of labeling it as a gaming system, they marketed it as a toy as not to fall into the negative image created from the game crash – it worked. Another major development from Japan was the Sega Mark III. This unit saw its success mostly in Europe and South America, but it still had a decent life here in the states.

Interestingly though, the US game industry suffered from the game crash in 1983, and many of the studios dried up and vanished. A key example of a major failure at this time was Atari’s E.T., based on the blockbuster movie. This game was a complete disappointment and couldn’t sell – thousands and thousands of units ended up in the landfill. It’s a fairly iconic piece of gaming history as it is often labeled the worst game ever made. Production and development in Japan, however, was just taking off and created a pretty healthy import market. This helped keep the arcade scene alive and well for several more years, and absolutely raised the consumption of console gaming at home. Nintendo was created during this time, and released its first home console, the Family Computer (Famicon). This device was a hit overseas, and when when distributed to the U.S., it was re-branded as the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES), and instead of labeling it as a gaming system, they marketed it as a toy as not to fall into the negative image created from the game crash – it worked. Another major development from Japan was the Sega Mark III. This unit saw its success mostly in Europe and South America, but it still had a decent life here in the states.

From the NES release in 1983 to the mid 1990’s, the third generation, games were created in 8-bit units. This kept the games in a relatively simple lo-fi package. Game play was typically side and/or vertical, ofetn with scrolling backdrops. Graphics were quite basic – the pixel was the primary hero at this time. The gamepad had replaced the previous controllers and keyboards, offering directional thumbpads and multiple buttons to increase functionality for gameplay feedback. This new era rushed in many award-winning titles such as Super Mario Bros., Mega Man, Metroid, Final Fantasy and of course, The Legend of Zelda.

With the game industry looking up and up, and regaining its feet in pretty much all world markets, development really started to progress and gain momentum. The fourth generation moved into 16-bit units, meaning the games could run faster, hold more memory and graphics could be substantially upgraded. Audio, however, still maintained a pretty low fidelity This era saw the first basic 3D games. Though the renderings were still somewhat basic – polygons with simple shading and materials, it brought a whole new dynamic to the user experience. The CD-rom also surfaced at this time, and made its way into some consoles, providing greater delivery of content, cut-scenes and data speed. Another major breakthrough was the introduction of hand-held gaming with Nintendo’s Game Boy and Sega’s Game Gear. The games could now be taken out of the living room and played virtually anywhere.

With the game industry looking up and up, and regaining its feet in pretty much all world markets, development really started to progress and gain momentum. The fourth generation moved into 16-bit units, meaning the games could run faster, hold more memory and graphics could be substantially upgraded. Audio, however, still maintained a pretty low fidelity This era saw the first basic 3D games. Though the renderings were still somewhat basic – polygons with simple shading and materials, it brought a whole new dynamic to the user experience. The CD-rom also surfaced at this time, and made its way into some consoles, providing greater delivery of content, cut-scenes and data speed. Another major breakthrough was the introduction of hand-held gaming with Nintendo’s Game Boy and Sega’s Game Gear. The games could now be taken out of the living room and played virtually anywhere.

Through the mid to late 90’s, consoles saw big upgrade in performance with 32-bit and 64-bit units, called the fifth generation. 3D graphics were enhanced and accelerated, audio saw significant improvements and you could now include more than two players during with some games. Sony’s Playstation and Sega’s Dreamcast were in competition with the Nintendo 64, and the arcade scene was witnessing its demise. Game studios were investing in big-budget projects during this time, with strong emphasis on story development, graphics and animation and sound design – including a greater appearance of star-studded voice talent.

During all this time, the PC industry was hard at work incorporating gaming into its user base. It was an obvious match, with the power that the larger processors, amount of RAM and better video cards that were advancing in the marketplace alongside the computers. Like the consoles, PC games had a very rudimentary start. Some early iterations were text-based adventure/mystery games, but quickly moved into more advanced simulators and platform deliveries, as well as Multi-user Dungeons (MUD) and eventually Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing games (MMORPGs). It wasn’t long before this portion of the industry began to thrive. With the widespread access to the internet, the computer gaming industry locked into a new realm of player interaction and competition. This online infusion also meant that users could directly access games without the need for cartridges or discs for game deployment. PC makers began production of desktop towers that were designed explicitly for the gaming experience, and this fueled the market of core components like video cards, cooling systems, controllers, monitors/displays, etc., and the race to make these all faster and better was on.

One of the major games to really help push the PC gaming market forward was Doom. Doom opened up the possibility of modding – modifying aspects of/adding elements to games or ROMhacks, and became very popular with the PC gamers. Many could even create their own maps and share them, helping to build a strong and thriving modding community. Even developers started modifying their favorite games and offering them out to the community. Today’s STEAM platform is a great example of the PC market’s popularity due to it’s openness and flexibility and connection to a huge dedicated group of users/players/developers.

The next natural target platform for games was the mobile phone. The first runs were again super basic – reliant on big pixels on low resolution screens. But the perfect environment for games like Tetris and Snake. And again – the draw by phone users to play games led that industry to push the boundaries of the hardware and software components used in these tiny devices. This really was the time when the electronics developers made astonishing steps in the miniaturizing of master components for hand-held computing. Microcomputers and microprocessors, flash storage, solid state hard-drives and smaller high-definition screens have contributed to the immense boom of mobile gaming and interactivity. With this, the new millenium ushered in the new craze of smartphones and tablets, like Nokia’s N-series in 2005 and Apple’s iPhone in 2007. Alongside these new gadgets came digital app stores introduced by tech giants like Google and Apple. These venues offered games and apps at a surprisingly affordable cost – causing small independent developers and studios to significant power and placement in an industry that was predominantly run by the big guys.

This brings us to date, where we are witnessing the mobile gaming revolution, massive online playing environments, a super strong presence in the PC sector, and new emerging forms of interactivity and entertainment. The home console industry is in its eighth generation, with powerful systems from the big companies – Sony’s Playstation 4, Nintendo’s Switch, Microsoft’s XBox One to name a few. These units are delivering HD to 4k graphics that rival the images and animation in the best film studios, full definition surround sound, seemingly endless creative worlds to explore and wildly fun gameplay. But what is more impressive are the breakthrough forms of input and output for these gaming experiences. Most consoles now come with cameras, enabled with infrared technology, motion detection sensors and spatial mapping abilities. Virtual reality headsets are commonplace with these units, allowing the players to completely visually immerse themselves in the world of their choice. New interactive controllers and sensors allow us to see our hands during gameplay and virtually touch, push, carry or communicate with objects, other players or weapons. This is new tech that again will only improve with demand and dollars.

Please watch these two short videos about Nintendo and SEGA during their very competitive times of the second and third generations of video gaming.

It’s hard to say exactly what the future of gaming will look like, and there are an overload of opinions out there, as you might guess. Virtual reality is a current reality, and it’s going to be around and getting better while we read this. Augmented reality is also playing a role in today’s gaming and interactive industry, and it, too, will show great signs of progress and development. There are many engineers and studios exploring ways to get the human body to be an integral component in this realm, instead of being relatively anchored like it is now.

Watch this short video with Ghislaine Boddington from body>data>space as she talks about her research in the body and its connection to emerging interactive technologies.

Please read this article by Patrick Stafford about what to possibly expect in the game industry in the next 5 years.

Many students involved in digital arts and technologies have a strong interest in getting into the gaming industry. Makes sense, as it is a growing and successful creative field, and so many of us just love games. There is more and more opportunity to get a foot in this door, but this usually means a move is necessary at least for a few years in order to get established at a solid studio and earn a good reputation before you can consider yourself a freelancer and “work from anywhere”.

The following is a list of the most common job roles in the video game world, a sampling we pulled from www.creativeskillset.org. If you feel you have an interest in or want to know if you have the qualifications for a specific role, visit their site and look into these descriptions in detail.

Animator: Being responsible for the portrayal of movement and behaviour within a game, making best use of the game engine’s technology, within the platform’s limitations. Most often this is applied to give life to game characters and creatures, but sometimes animations are also applied to other elements such as objects, scenery, vegetation and environmental effects.

Assistant Producer: The Assistant (or Junior) Producer works with a game’s production staff to ensure the timely delivery of the highest quality product possible. Typically, they will focus on specific areas of the development process. This could involve handling the communications between the publisher and developer, or co-ordinating work on some of the project’s key processes such as managing the outsourcing of art assets.

Audio Engineer: The Audio Engineer creates the soundtrack for a game. This might include music, sound effects to support the game action (such as gunshots or explosions), character voices and other expressions, spoken instructions, and ambient effects, such as crowd noise, vehicles or rain.

Creative Director: The Creative Director is the key person during the game development process, overseeing any high-level decisions that affect how the game plays, looks or sounds. In many cases, the Creative Director is also the creator of the original game concept and characters, and so makes sure that the finished game fulfils the initial goals.

DevOps Engineer: As games begin to become more and more focused on online features, it’s becoming vital to have an engineer dedicated to creating and maintaining that infrastructure. Due to the way games are run, each individual user of a multiplayer or online game will have an instance of the game running locally that interacts with web services in the background. This may be something as simple as the price of an item in an online store fluctuating for different players, or as complex as combat systems that combine inputs from multiple players to determine who is the winner!

A DevOps Engineer is responsible for making sure all of this works cohesively for all the players. Most DevOps developers will design and build the entire system themselves, either alone or with a team.

Game Designer: Game Designers devise what a game consists of and how it plays. They plan and define all the elements of a game: its setting; structure; rules; story flow; characters; the objects, props, vehicles, and devices available to the characters; interface design; and modes of play. Once the game is devised, the Game Designer communicates this to the rest of the development team who create the art assets and computer code that allow the game to be played.

Game Programmer: Game Programmers work at the heart of the game development process. They design and write the computer code that runs and controls the game, incorporating and adapting any ready-made code libraries and writing custom code as required. They test the code and fix bugs, and also develop customised tools for use by other members of the development team.

Different platforms (games consoles, PCs, handhelds, mobiles, etc.) have particular programming requirements and there are also various specialisms within programming, such as physics programming, AI (artificial intelligence), 3D engine development, interface and control systems.

Game Artist: Artists create the visual elements of a game, such as characters, scenery, objects, vehicles, surface textures, clothing, props, and even user interface components. They also create concept art and storyboards which help communicate the proposed visual elements during the pre-production phase.

Lead Artist: The Lead Artist is responsible for the overall look of the game. Working with the Game Designer and Lead Programmer, the Lead Artist devises the game’s visual style and directs the production of all visual material throughout the game’s development. They produce much of the initial artwork themselves, setting creative and technical standards and determining the best tools and techniques to use.

Level Editor: The Level Editor defines and creates interactive architecture for a segment of a game, including the landscape, buildings and objects. They must be true to the overall design specification, using the characters and story elements defined by the Game Designer, but they often have considerable freedom to vary the specific look and feel of the level for which they are responsible. They define the environment, general layout of the spaces within the level, and lighting, textures, and forms. They define the characters and objects involved, whether they are player-controlled or non-player characters, and any specific behaviours associated with the characters and objects.

The Level Editor also develop the gameplay for the level, which includes the challenges that the characters face and the actions they must take to overcome them. The architecture helps to define those challenges by presenting obstacles, places to hide, tests of skill, and other elements to explore and interact with.

Narrative Copywriter: A Narrative Copywriter is a writer for a videogame. Due to the extreme focus on game design during development, it’s a Narrative Copywriters job to make sure that story elements work within the design choices. For example, if the designer decides that they want social media integration, a Narrative Copywriter may decide to work in a story reason.

They will also be responsible for helping to shape the overall story and write character dialogue. It’s important for the Narrative Copywriter to understand the tone and world of the game, as they’ll be writing a lot of the small touches than could make or break the experience.

QA Tester: Quality Assurance Technicians, or Testers, perform a vital role. They test, tune, debug and suggest the detailed refinements that ensure the quality and playability of the finished game. They play-test the game in a systematic way, analysing the game’s performance against the designer’s intentions, identifying problems and suggesting improvements.

They test for bugs in the software, from complete crashes to minor glitches in the program. They also act as the game’s first audience, reporting on its playability and identifying any aspects which could be improved.

Playing games all day for a living might sound like an ideal job, but this is in fact a highly disciplined role.

Technical Artist: The Technical Artist acts as a bridge between the Artists and Programmers working on a game. They ensure art assets can be easily integrated into a game without sacrificing either the overall artistic vision or exceeding the technical limits of the chosen platform. The role is a relatively new one for the games industry, but is becoming increasingly important as consoles and PC hardware becomes more complex.

Despite their technical knowledge, the Technical Artist works part of the art team, working closely with the Lead Artist and the Creative Director, as well as the Lead Programmers.

Meet some creatives in the game industry.